Breeding for Type

Genetics Mini-Series Article #11

More important than egg color, feather color, shank color, or any other such decoration is type. Type refers to the general shape and conformation of the bird. However, type is not controlled by neat, Mendelian-type genetics which can be sketched out in a Punnett square. Body shape, including skeletal structure, muscling, and feathering, is controlled by many, many genes, each combination creating a subtle gradation of a given feature. Therefore, body type is bred through selection: Breed your best to your best.

When extremes of body types are bred together, such as a bantam cockerel and a standard rooster, offspring can be intermediate in size or closer to either of the parents. The next generation may show even more variability. Thus, is it best not to breed extremes in hopes of an intermediate but to slowly move closer to the shape that you want.

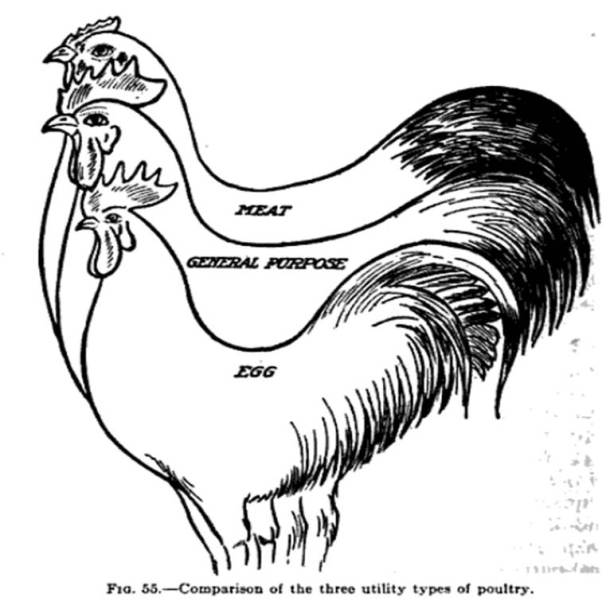

Each breed has a specific type. This is why a Dominique and a Barred Plymouth Rock are two different chickens even though they are both barred with yellow legs and brown eggs. Their shape is a large part of their breed identity. These shapes are described by the American Poultry Association in their Standards of Perfection. Type can also be described in terms of purpose. Egg-laying types have a thinner skeleton, smaller frame overall, a boxier shape, and a deep, soft abdomen. Meat-types have a thicker frame to support heavier muscling, a rounder shape, and a tighter abdomen.

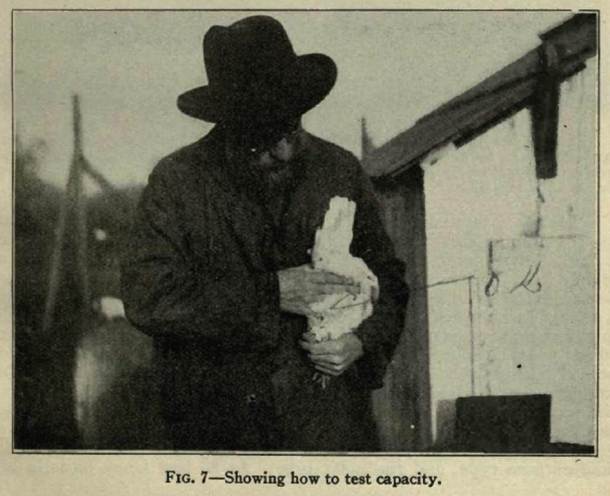

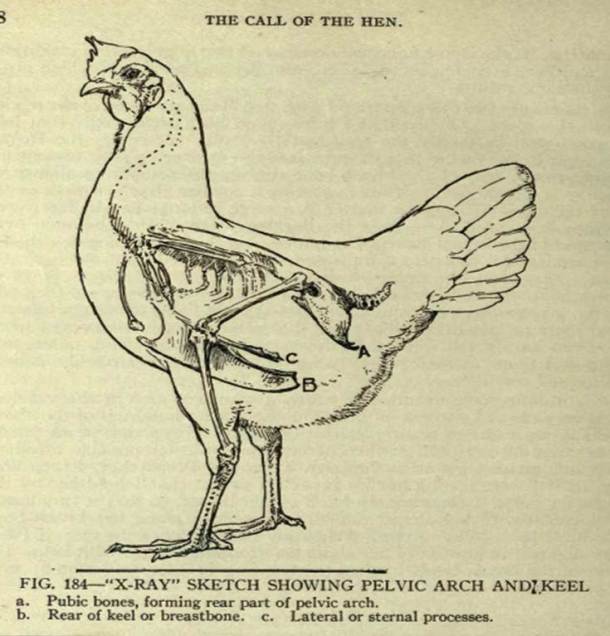

In the 1913 classic Call of the Hen, Walter Hogan describes his method of selecting poultry for egg production traits. He puts his hands on each bird, measuring and probing for specific traits which indicate productive capacity. These traits include the width of the pelvic bones (thinner is better for egg production, about ¼”), width between the pelvic bones (more is better), space between the pelvic bones and the keel (more is better), and condition of the vent (moist, full is better than dry and puckered).

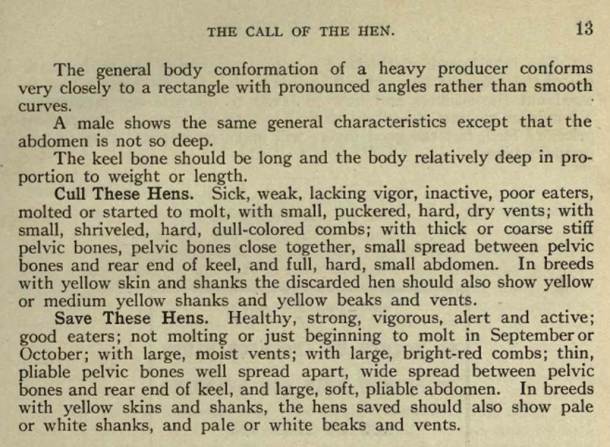

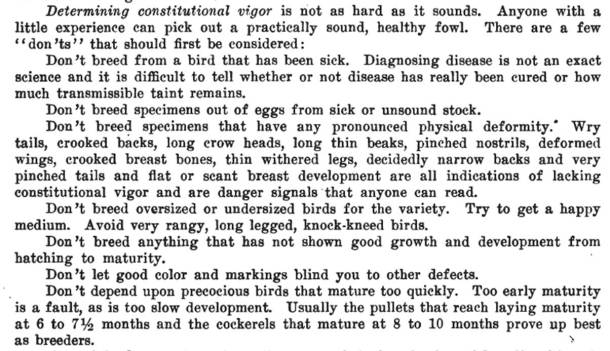

Constitutional vigor is also an important consideration in selection. Healthy, vigorous chickens who are able to make good use of their food and fight off disease are preferable to chickens who eat a lot to produce little and get sick. In his article in the 1915 American Poultry Yearbook, Prince T. Woods lists features to select for and against to ensure good constitutional vigor. You can find his recommendations at the bottom of this article.

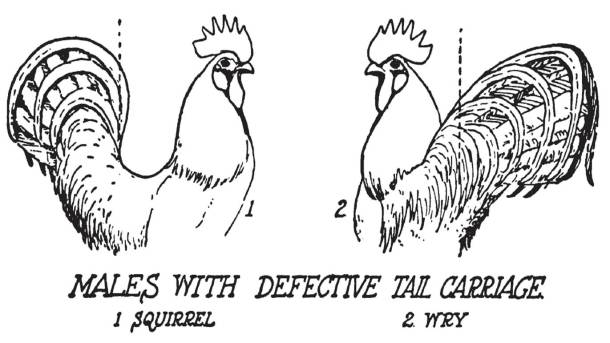

There are structural faults which are important to select against. A wry tail is a tail usually held to one side or another. Sometimes this is accompanied by roach back, where the spine curves up to make a hump near the tail. A squirrel tail is held more than 90 degrees above horizontal, and a split tail appears to be split down the middle when you look down on it from above, curving out towards either side.

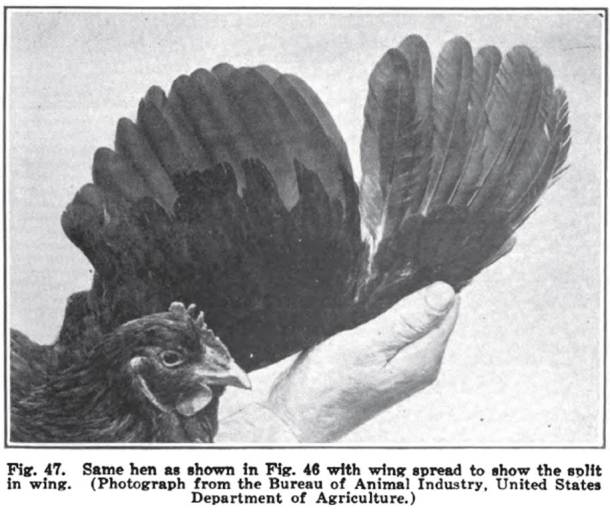

When you hold a chicken’s wing extended, you may notice a split wing where there is a gap between the primary and secondary feathers; it almost looks like two separate wings with a deep gap in the middle rather than a nice smooth curve from the tip of the wing into the body. This is another trait to select against.

Some birds have a crooked keel which is usually genetic although it can be exacerbated by roosting issues. (In general, later exposure to roosts and wider roosts of 3” wide or more reduce the chance of developing a crooked keel.) This is something you will only notice by holding the bird and running your hand down its ‘breastbone.’

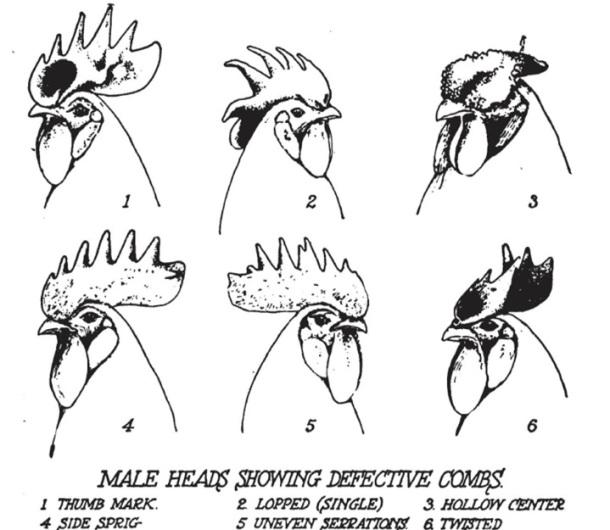

The shape of the head is also important. A crow head is shallow from top to bottom, like it has been squished whereas a desirable head has depth. The comb can be split like a wing, have a thumb-print like indentation, have side sprigs which are points or bumps sticking out of the sides, or a twist.

It is best not to breed any bird that has had curled toes, splay legs, or any other physical defect. While it is true that these things can be due to incubator conditions or nutrition, every part of that chicken’s body has been affected by those same negative conditions. Malnutrition and environment can affect cell development and even DNA replication which can in turn affect the quality of genetic material handed down to offspring. (To learn more, take a look at epigenetics.)

Along the same line, providing optimal nutrition to breeders will result in a healthier flock from generation to generation. Breeders need more protein, fatty acids, and greens than a bird who only needs to produce an edible egg (see Feeding Breeders). (For the same reason, human mothers and fathers need enhanced nutrition often provided by a prenatal vitamin, and yes, I said fathers, too.) Meats, including fish, make good supplements during breeding season as well as greens like alfalfa and extra protein in hard boiled eggs or black oil sunflower seeds.

Chose birds that have all of these desirable traits, but keep in mind that a hen who is laying heavily will never look as good as a hen who is not laying because she is putting much of her nutrition into her eggs rather than her plumage or shank color. A hen who is laying well will have a loose abdomen (which looks like a sagging, soiled diaper to me), a loose-looking comb, a moist, soft vent, and bleached coloring overall, especially in yellow-skinned breeds. A yellow-skinned hen who has been laying will grow paler and paler and even look white; it would be a mistake to cull her for this unless you would rather not breed chickens to lay eggs! Feathers and leg color will always look best after a period of non-laying.

This is the second-to-last article in the Genetics Mini-Series. The twelfth and final article will be next week – an even dozen.

Recommendations from the 1915 American Poultry Yearbook, Prince T. Woods (digitalized by Google):

![By Sue Clark (Flickr: chickens) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://i0.wp.com/upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e2/Chickens.jpg)

![By L. Prang & Co., Boston [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://i0.wp.com/upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4f/The_poultry_of_the_world%2C_1868.jpg)

Pingback: GMS12: Inbreeding Coefficients « Scratch Cradle

Pingback: Which Rooster? « Scratch Cradle

Pingback: GMS Supplement #3: Selecting for Head Shape « Scratch Cradle

Pingback: Setting Up Breeding Pens Part 2 | Scratch Cradle

please show pics of roach back